In grad school, I elected to write a literature paper about Paul Auster's Leviathan. I came to class ready to discuss the novel, certain I'd understood what Auster was getting at, only to learn of the existence of Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and to hear how Auster was reflecting that pivotal work. I sat there for a while, listening, and then raised my hand and explained that I'd believed the leviathan of the title was a sea monster, i.e. the whale that swallowed Jonah, and that allegorically that monster was a national fear and despair lurking under the scrim of American life in the late 20th century. No matter how wrong the class lecture told me I was, I still thought this was a valid theory of the novel. The professor, bless her heart, encouraged me to write my final paper on this theory. And I did.

In my reading, the leviathan is a societal force. It resembles a beast of the deep, in that it is invisible, massive, and dangerous. It is large enough to gulp its victims without even stretching its jaws. The leviathan, this societal force, is the loss of identity suffered by the Baby Boomers when they discovered their failure to make lasting change, and it’s their dawning realization of mortality.

(me, 2014)

I was embarrassed that I'd missed the point Auster had built into the book, but as I researched and wrote the paper, I came to believe that my point of view - although informed by contemporary ideas and influences rather than those of a classical Western education - was valid, too. I wrote about Vietnam, the atomic bomb, and President Carter's "crisis of confidence" speech. I got an A, as I recall.

*

Lars von Trier first caught my eye in the early aughts with Dancer in the Dark. Good God did I hate that movie. I was young, and obsessed with Björk, and utterly infuriated that the bad guy won and the good girl lost. And while I understood what von Trier was getting at by shooting lush, stationary musical numbers vs. stark, wobbly handheld real life, it didn't keep me from being annoyed by the handheld sections.

Some years later, everyone went on and on about Melancholia, so I saw it. My favorite part was the tableaux that open the film: slomo textures and painterly colors, in weird scenarios, flawlessly composed. The whole wedding section, shot in handheld not-great DV, I could not make head or tail of; why would he shoot something so ugly and annoying and dragged-out when he could provably make such beautiful pictures? The third section was more comprehensible, but still puzzlingly long and odd.

More years passed. In 2021, I noticed while browsing Kanopy that both volumes of Nymphomaniac were available, and I had a strong guess that they wouldn't be for long, so I watched them. Snap. Everything fell into place. I don't know if it's because I'd watched Funny Games (2007) and absolutely loved it, reframing my sense of what extremity in film does and how it works, or because I'd simply gotten older, but I found Nymphomaniac a profound work, and a necessary one. One of those films that stretches cinema beyond entertainment, that makes itself a text to pore over. And that it was an extreme film, a blasphemous film, was part of its intellectual intentions! Oh, this trolling Dane, how I suddenly admired him.

Deciding to start fresh, I watched Breaking the Waves, von Trier's breakthrough and still probably his most well-regarded film. It opened up my understanding of his reputation, and confirmed what I thought he was up to, but I didn't connect to it as much.

Yesterday I watched The House that Jack Built. This review warned me away from it, but that review is wrong, I believe, and falls exactly into the trap that von Trier has set for the viewer.

VERGE:

No. No, no, no! You're constantly trying to manipulate me.

And with children, the most sensitive subject of all.

Don't let him manipulate you! I want to shout at Richard Brody. See past your emotional reflex and turn on your brain.

The central juxtaposition of House is violent death as an art form. Jack says this himself, repeatedly, trying to convince Verge that his project is to make art from murder. Verge insists that art springs from love. (Verge is Virgil, the greatest poet of antiquity, and Jack is a serial killer. Who would seriously believe von Trier positions Jack to win the argument?)

I recognized that the sacred (art) is the profane (violent death) in this film. I had previously hypothesized that Nymphomaniac intended to make a saint out of the title character: a saint of sex, someone for whom sex is an all-encompassing, glorified pursuit. (She even has a wound that refuses to heal!) The conversation between Joe and Seligman is a religious debate, about fishing and sex and God and love and life itself; it's a debate between extremes - the debauched and the pure - but what's pure and what's debauched shifts over the course of the film. In Dancer in the Dark, an absolute innocent commits a brutal murder (and the most luscious visuals exist in the mind of the blind woman). In Melancholia, Justine's depression debilitates her, but she is also voluntarily in thrall to it - in love with her own sorrow. In Breaking the Waves, God gives Bess a mandate to commit sin.

I started to see von Trier's project as crashing together two abstract ideas that it would be blasphemous (literally or culturally) to consider in the same breath. Sex and death is an old, easy collision for film, but sex and saintliness? Innocence and violence? He's doing extreme cinema, but the characters' behavior - the sex and violence, in graphic detail - is a ruse. The extremity is in putting together ideas that have traditionally remained far apart, in considering them as reflections of each other. It's sort of Hegelian, and sort of deconstructionist, but (impishly and) productively so, in a way that doesn't leave the deconstructor with a vacant lot.

Yet.

As ever when I have ideas like this, where I think I've figured out what makes challenging art hang together, I remember Leviathan. Someone else has probably figured out the metronome of this art, and it's probably a more classical rhythm than I could recognize. Not knowing Hobbes, that day, will haunt me forever.

Then again, I found support in the text and in other scholarly articles for my theory of Auster's novel. I argued that theory successfully, in my own small context.

|

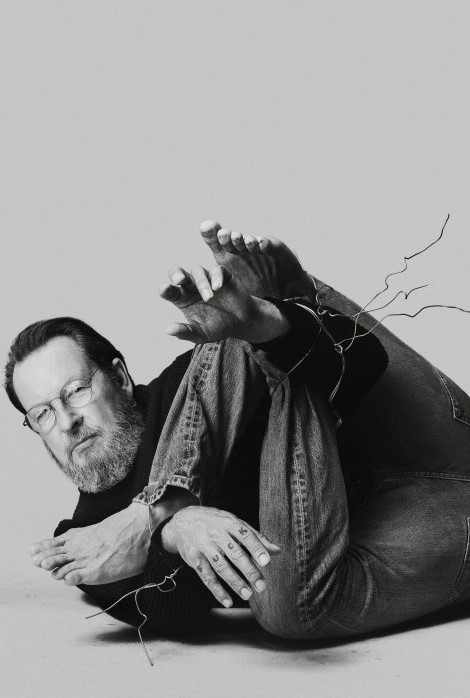

Lars von Trier in a promo photo for The House that Jack Built. Knuckle tattoo is not pshopped |

At the end of all this thinking and developing, I don't want to look up the prevailing theory of von Trier's cinema. I don't want to learn that I'm either parroting an established idea or that I'm dead wrong. I'd rather hang out here, where I semi-privately think I have a good idea that helps me understand a challenging group of artworks. I don't want to be Pauline Kael, so idiosyncratic that she can't really be trusted. As a critic I try never to lead with my ego or my unique reactions - otherwise I'd gush about Gothic literature and melodramas, insist that Shutter Island is better than Goodfellas. I know better than to confuse those preferences with informed criticism.

On whose authority am I right or wrong about Lars von Trier, anyway? Yours? His? Richard Brody's? Please. A consensus about art is fragile and temporary. I'd like to know about that consensus, and perhaps be informed by it, but being part of it doesn't sound appealing.

So I shall declare that I loved The House that Jack Built, and that I think von Trier is much less of a troll than he is creating art via unusual variants on thesis/antithesis. There's some trolling, sure, but not the malignant kind. Around 2005, he said a film should be like a stone in your shoe, and no matter how hard I squint, I can't find a way to disagree with that sentiment.